kirisutogomen (![[personal profile]](https://www.dreamwidth.org/img/silk/identity/user.png) kirisutogomen) wrote2012-04-22 07:32 pm

kirisutogomen) wrote2012-04-22 07:32 pm

Entry tags:

Becoming Human

(excerpt from Ian Tattersall's Becoming Human)

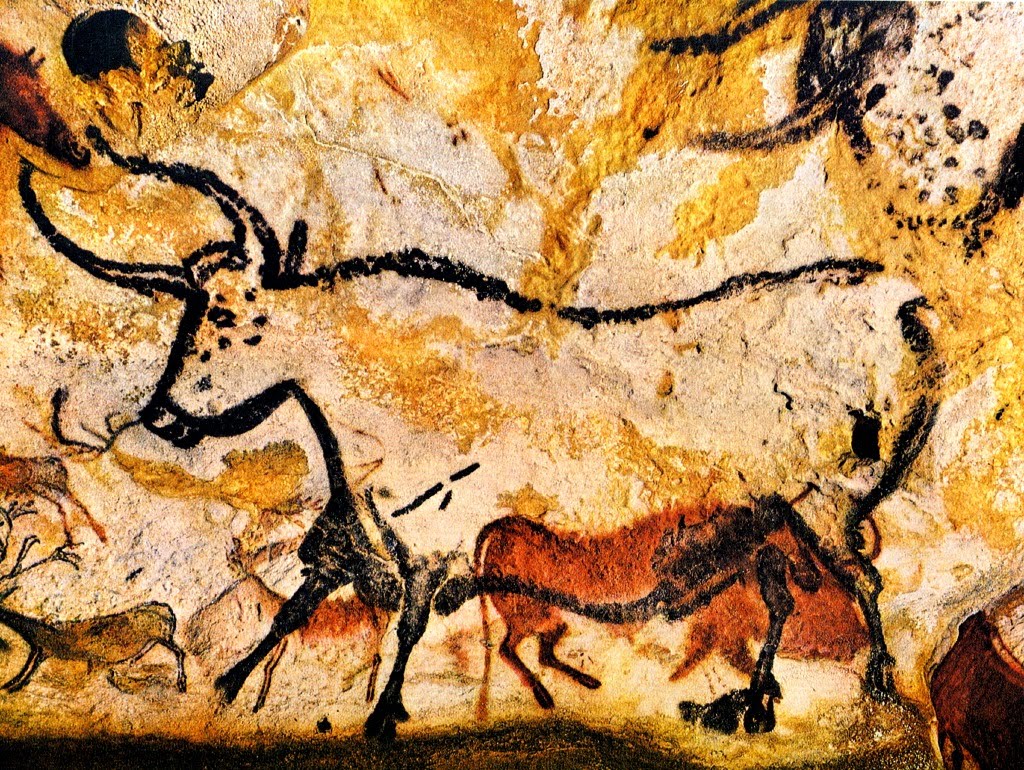

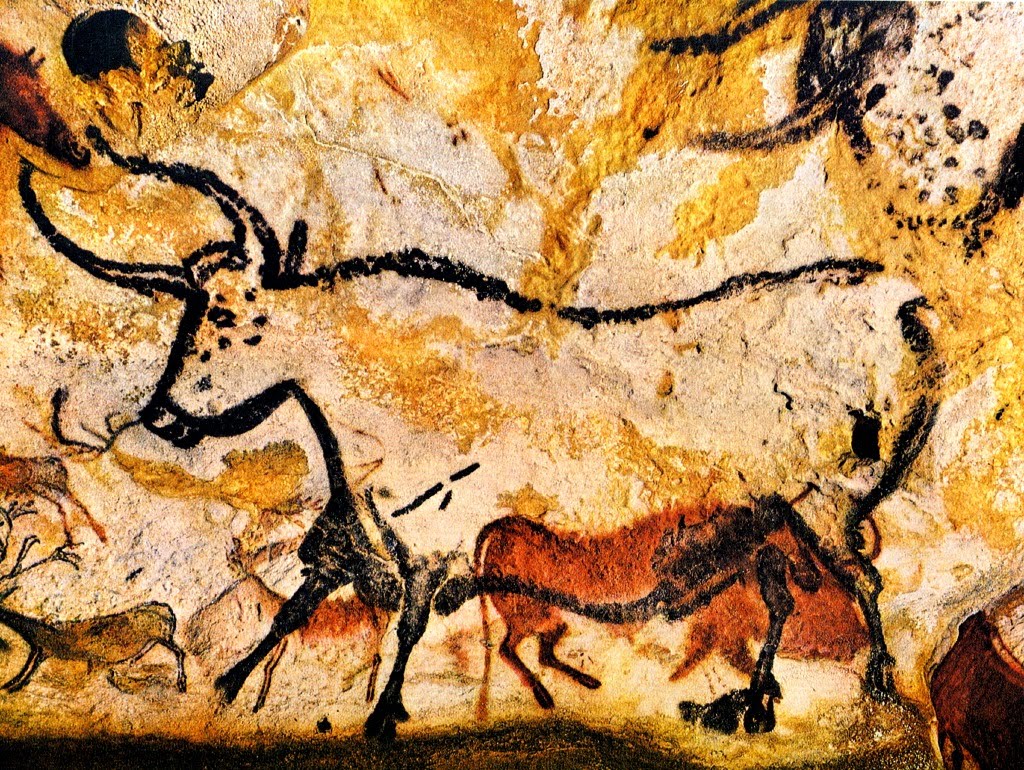

Combarelles I is a site from the Magdalenian culture, a culture that existed in various forms over much of non-glacier Europe for over seven thousand years. The famous cave paintings at Lascaux are also Magdalenian, from thousands of years before Combarelles I. Even though Combarelles I is all engravings and Lascaux is all paintings, from thousands of years apart, mysteriously they share certain characteristics: neither depict any landscape or vegetation, just large mammals, interspersed with many carefully executed geometric figures. Some mammals such as bison, aurochs, and horses are present in great numbers, while the caribou that were more numerous than any other large mammal and who were the only large mammal the Magdalenians hunted are depicted rarely. (Bison didn't even live in these mountainous regions, roaming instead across prairies hundreds of miles to the north.) While human representations are common in sculptures or outdoor rock face art from the period, human figures almost never appear in deep cave art. However, stenciled negative hand images, made by spitting paint at and around a hand pressed palm-first against the cave wall, are quite common. Many of the hands are clearly those of children. The Magdalenians did not live in the caves where their art was; they lived either in other rock shelters or the teepee-like tents appropriate to nomadic hunter-gatherers. These various characteristics are consistent over a period of time thousands of years longer than the span from the invention of the wheel to today.

And if that doesn't blow your mind, the Chauvet Cave paintings are dated to over 30,000 years ago. One thousand generations ago, people made hundreds of paintings of a dozen different animal species, mostly predators, including lions, bears, panthers, and owls. Incisions and etching along the outlines of some figures create an appearance of depth and an illusion of motion as your flickering light source casts shadows around the edges of the animals. Werner Herzog made a 3-D film called Cave of Forgotten Dreams about the Chauvet Cave, inspired by a New Yorker article, "First Impressions", by Judith Thurman.

Personally, I have no taste for most visual art. Great masterpieces leave me cold; I look at a Gauguin and say, "yup, that's a naked lady all right, although she's kind of funny-shaped". But the thought of these artists, tens of thousands of years ago, crawling for hours through dangerous crevices solely for the purpose of creating, in conditions far less comfortable than a Manhattan art studio....that sends shivers down my spine.

I doubt we'll ever really understand why for thousands of years the rules allowed cave artists to depict bison and lions but never trees or people, nor why small children would need to be brought to the nearly inaccessible art; the answers are just too dependent on too much detailed cultural context for us to ever grok it. But one thing seems clear, that the artistic impulse is deeply embedded in our natures. I don't know if it's genes or memes, but something transmissible has burrowed down into our psyches deep enough that we're probably never going to lose it.

The Boston College Arts & Mind Lab (aka the Winner Lab, after the principal investigator, Ellen Winner (who also happens to be the chair of the BC Psychology Department as well as a senior research associate of Project Zero)) does research on "the psychological components of involvement in the arts". In particular, the Lab Manager, Jen Drake, is investigating the function of art in "mood repair", i.e., short-term emotional benefit, mostly about using creative expression as a device to improve mood from low levels. Well, actually Jen is busy preparing to defend her PhD thesis, so she isn't actively running the experiments at the moment, but she has some capable undergrads managing things for her in the Living Laboratory (explanation of which here). (Actually she may have already had her thesis defense. I think it was supposed to be sometime in April.) Anyway, what they do is induce a temporary low mood inthe test subjectyour precious child, by getting them to focus on a memory of a disappointing event, then applying some sort of treatment, and then measuring any change in self-reported emotional state. One interesting variant of the experiment compared the relative benefits of cathartic/venting expression, e.g., drawing a picture of the disappointment, vs. distracting expression, e.g., drawing a picture of an irrelevant house. Another involved comparing artistic distraction vs. other forms of distraction (e.g., GameBoy Tetris). Then there was one which compared the effects of choice; the subject is asked which of the house-drawing or Tetris-playing they would prefer for mood repair purposes, and then in one condition the subject is allowed to engage in the preferred activity while in the other condition subjects have to do the one they dispreferred. I believe their preliminary results from that one indicate that if anything choice is slightly unhelpful. We have no idea what makes us happy, even if we think we know.

A leisurely half hour's stroll outside the sleepy southwestern French town of Les Eyzies de Tayac, a narrow fissure penetrates deep into a limestone cliff face. The path of an underground stream, this tortuous subterranean passage is the cave of Combarelles I. At its entrance, a guide unlocks an ancient iron grille and swings it open. Beyond, a low, narrow winding tunnel disappears into the gloom, barely high enough to stand up in or wide enough to squeeze past your neighbor. Weaving and ducking, you proceed a hundred and fifty yards along this somber passage, wondering why on Earth you have come to this cramped, forbidding place, dark despite being lit at intervals by electric lights.

Suddenly the guide stops, and all your questions vanish. Under the oblique light of filtered lamps, the walls of the cave suddenly come alive with engravings, some of them almost obscured by a calcite coating deposited on the cave walls over the millennia. Horses, mammoths, reindeer, bison, mountain goats, lions, and a host of other mammals cascade in image along the cave walls over a distance of almost a hundred yards, over three hundred depictions in all. Delicately executed and meticulously observed, these varied and overlapping images were made by people of the late Ice Age, perhaps thirteen thousand years ago.

You are mesmerized, not simply by the subtlety of these marvelous engravings---done at a time when the landscape around Combarelles, now oak forest, was open steppe roamed by mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, and cave lions---but by their sheer ancientness. For this is not in any sense crude art; it is art as refined in its own way---and certainly as powerful---as anything achieved since. Any preconceptions you may have had of the "primitiveness" of "cavemen" are instantly dispelled. When you finally tear yourself away from these superb relics of an unimaginably remote human past and turn to grope your way back to the cave entrance, you notice something else. Halfway up the cave wall, the nature of its surface changes. The bottom of the cave has been dug out in this century, to make it easier for you to visit. When the Ice Age artists entered the cave, in was in places less than two feet high. These early people had had to squirm their way in on their bellies, squeezing between the cave's ceiling and floor, doubtless gasping for breath in the oxygen-poor air. Once a distant point had been chosen for decoration after the best part of an hour's uncomfortable crawling, the artists barely had room to move their arms, let alone the rest of their bodies. At the same time, they must have carried with them into the cave not only the flint tools that they used for engraving, but unwieldy and unreliable sources of light. Illumination, as we know from other sites of similar age, was supplied by lamps consisting mostly of hollowed-out slabs of rock (occasionally quite elaborately shaped and decorated), in which lumps of animal fat burned through juniper wicks. Though feeble and easily extinguished, these guttering lamps must have added a remarkable effect to the engravings as the artists experienced them. For in flickering light such as they produced, the images seem to come alive, bouncing along the cave walls; and the artists rendered the animals in suitably active poses.

Leaving the cave, you are consumed with the question "Why?" Why wriggle and struggle along a constricted, choking, dark, uncomfortable, and potentially dangerous passage that deep-ends deep in the rock with barely room to turn around? Why create art that could only be revisited with the greatest of difficulty? Why virtually ignore the outer part of the cave, executing your art only in its far interior recesses?

Combarelles I is a site from the Magdalenian culture, a culture that existed in various forms over much of non-glacier Europe for over seven thousand years. The famous cave paintings at Lascaux are also Magdalenian, from thousands of years before Combarelles I. Even though Combarelles I is all engravings and Lascaux is all paintings, from thousands of years apart, mysteriously they share certain characteristics: neither depict any landscape or vegetation, just large mammals, interspersed with many carefully executed geometric figures. Some mammals such as bison, aurochs, and horses are present in great numbers, while the caribou that were more numerous than any other large mammal and who were the only large mammal the Magdalenians hunted are depicted rarely. (Bison didn't even live in these mountainous regions, roaming instead across prairies hundreds of miles to the north.) While human representations are common in sculptures or outdoor rock face art from the period, human figures almost never appear in deep cave art. However, stenciled negative hand images, made by spitting paint at and around a hand pressed palm-first against the cave wall, are quite common. Many of the hands are clearly those of children. The Magdalenians did not live in the caves where their art was; they lived either in other rock shelters or the teepee-like tents appropriate to nomadic hunter-gatherers. These various characteristics are consistent over a period of time thousands of years longer than the span from the invention of the wheel to today.

And if that doesn't blow your mind, the Chauvet Cave paintings are dated to over 30,000 years ago. One thousand generations ago, people made hundreds of paintings of a dozen different animal species, mostly predators, including lions, bears, panthers, and owls. Incisions and etching along the outlines of some figures create an appearance of depth and an illusion of motion as your flickering light source casts shadows around the edges of the animals. Werner Herzog made a 3-D film called Cave of Forgotten Dreams about the Chauvet Cave, inspired by a New Yorker article, "First Impressions", by Judith Thurman.

Personally, I have no taste for most visual art. Great masterpieces leave me cold; I look at a Gauguin and say, "yup, that's a naked lady all right, although she's kind of funny-shaped". But the thought of these artists, tens of thousands of years ago, crawling for hours through dangerous crevices solely for the purpose of creating, in conditions far less comfortable than a Manhattan art studio....that sends shivers down my spine.

I doubt we'll ever really understand why for thousands of years the rules allowed cave artists to depict bison and lions but never trees or people, nor why small children would need to be brought to the nearly inaccessible art; the answers are just too dependent on too much detailed cultural context for us to ever grok it. But one thing seems clear, that the artistic impulse is deeply embedded in our natures. I don't know if it's genes or memes, but something transmissible has burrowed down into our psyches deep enough that we're probably never going to lose it.

The Boston College Arts & Mind Lab (aka the Winner Lab, after the principal investigator, Ellen Winner (who also happens to be the chair of the BC Psychology Department as well as a senior research associate of Project Zero)) does research on "the psychological components of involvement in the arts". In particular, the Lab Manager, Jen Drake, is investigating the function of art in "mood repair", i.e., short-term emotional benefit, mostly about using creative expression as a device to improve mood from low levels. Well, actually Jen is busy preparing to defend her PhD thesis, so she isn't actively running the experiments at the moment, but she has some capable undergrads managing things for her in the Living Laboratory (explanation of which here). (Actually she may have already had her thesis defense. I think it was supposed to be sometime in April.) Anyway, what they do is induce a temporary low mood in